How to Become an Airline Pilot in 2026 (Updated Guide)

Learn how to become an airline pilot in 2026 with this updated guide. Training routes, costs, MPL vs ATPL, funding options, and airline advice.

With modern day aircraft becoming ever more complex, there’s such a vast array of things that can (although thankfully don’t very often) go wrong. It would be a hell of a task for pilots to know and follow an almost infinite number of unique procedures for every single possible failure combination.

Instead, the pilot training world has developed general frameworks that allows pilots to effectively handle a huge variety of failures, from relatively benign singular failures to extremely complex and potentially life-threatening ones involving multiple different problems. As well as building a framework, there is a heavy focus on the development of pilot competencies and behaviours, as these can better equip pilots to deal with a wider range of possible problems.

Whilst there are a few different failure management frameworks out there (DODAR, TDODAR etc), the one I’m sharing in this article is a combination of all the best bits of each model that I’ve found to be most effective over my 10+ year career. It’s the complete structure that I personally follow when faced with a failure management situation in simulator checks and when operating real aircraft. It’s also a valuable structure to have not necessarily just for failures, but also non-normal situations that require a change of plan. I’m not saying it’s the ‘right’ way, and certainly not the only way, however it’s one that’s helped me manage a huge variety of situations effectively so I’d like to share and explain it.

Failure management is something I knew nothing about before entering the airline industry and the below model is one I wish I’d been taught a lot earlier in my career. Hopefully this article will be helpful to those in that situation, but also with current experienced pilots looking to further develop their own failure management strategies. Below is a basic overview of the framework, I’ll then breakdown each part of the process in more detail, along with the top tips I’ve learnt over the last decade that have enhanced the effectiveness of the framework, all whilst also throwing in a few real-world examples to show its validity in action.

Although this framework is specifically for airline pilots, I firmly believe it can be applicable to pilots in other sectors of aviation, as well as transferable and insightful to other industries. I’ve included a specifically designed worksheet for pilots at the end of the post which has helped me through various simulator and real life scenarios.

Contents

ToggleBeing able to manage failures effectively requires pilots to possess certain competencies and behaviours that have been developed through training. I’ll go into these competencies in more detail in a different article, but for now it’s worth noting that whilst there really isn’t any substitute for a pilot possessing these competencies, having a framework to follow during a failure management situation can really benefit flight crew. Having a strong set of competencies will allow the situation to be handled even more effectively with a higher chance of a successful outcome.

For now here’s a link for more info on pilot competencies.

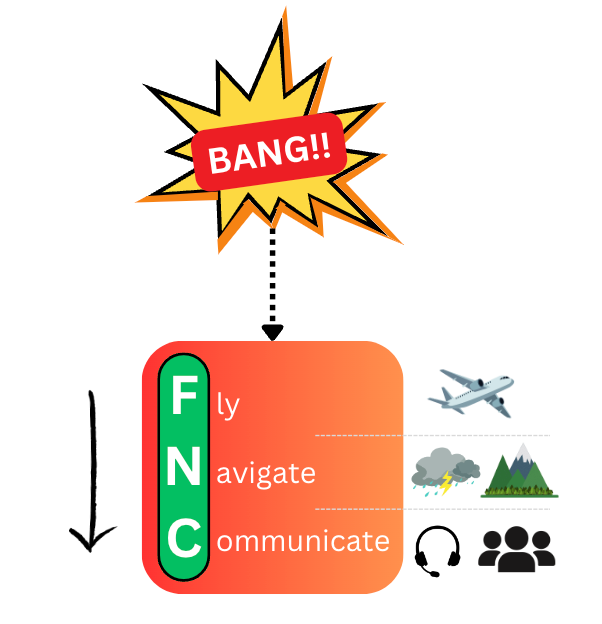

Now onto the process after something goes ding or bang:

These are your priorities, and in this order. Your crystal clear communication to ATC about your terrain warning system failing is not much use if you put the plane into the side of a mountain because you prioritised the radio call instead of focussing on ‘fly’ and ‘navigate’ first.

The aim of this step, otherwise known as 1 of 4 of Airbus’ Golden Rules for pilots, is to ensure it’s clear who’s in control of the aircraft, get the aircraft stabilized, on a safe trajectory, build your situational awareness & alert whoever immediately needs to know. It ensures you’re in a safe place to then dive ‘heads in’ and start the next part of the framework. Let’s break it down;

Fly

Navigate

Communicate

Top Tips for FNC

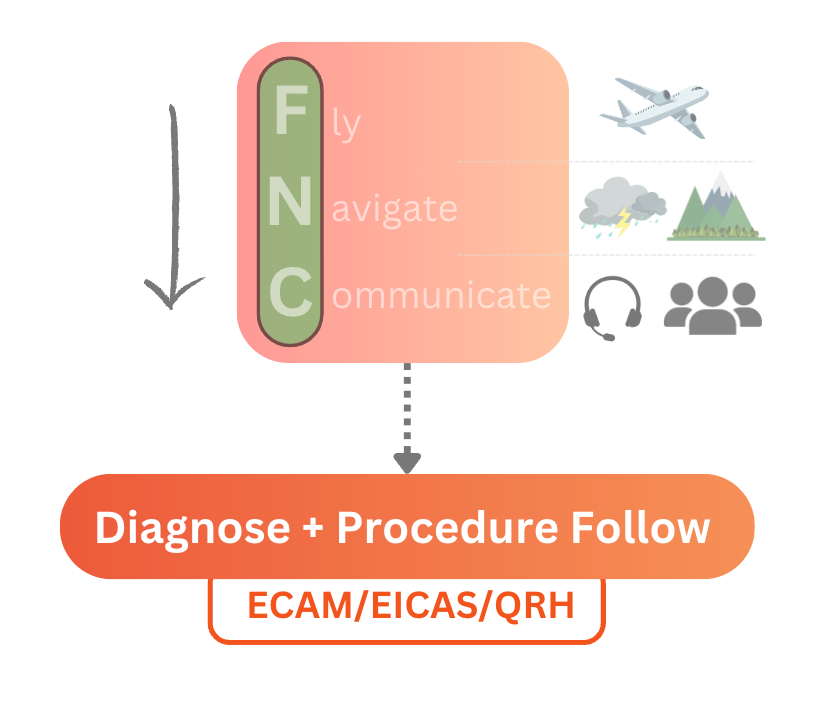

So, FNC completed. The aircraft is on a safe and appropriate trajectory. Both pilots are in the loop and anyone who needs to know, is in the know. Time to move onto understanding what the issue is.

With FNC complete, we now have the capacity to turn our attention to the problem. This step’s about diagnosing the issue, along with following any procedures dictated to us by the ECAM/EICAS or our QRH. There’s not too much to write about here as each diagnosis will be different, but you want to ensure you have a good understanding of what’s happened to the aircraft before moving to the next stage.

Top Tips for Diagnosing

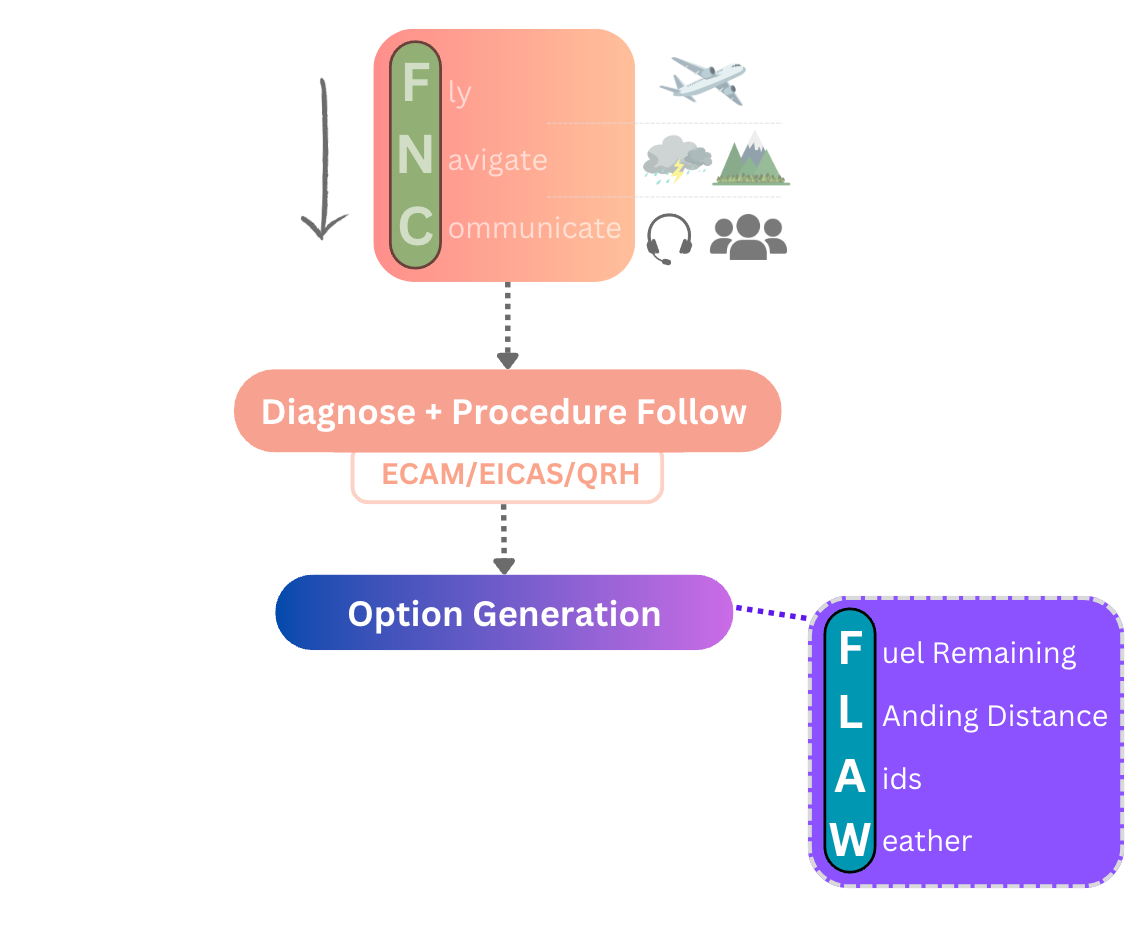

Now you understand what the problem is, you’ve followed any immediate procedure required by the manufacturer or airline, what now? You need to think about your options. Simply put, you have 3…Continue, divert or return.

The decision is likely to be made using a mix of good airmanship and the pilot competencies, along with recommendations from the aircraft or QRH as to how quickly you should be trying to get the think on the ground.

Sometimes the ‘right’ option is immediately clear, other times you may have to choose a ‘best’ option between multiples potential ones. There are some tools available to help you make this decision. One of them is FLAW:

Fuel – How much fuel do you have? What’s your fuel burn per hour? (issues like having the landing gear stuck down can drastically increase this) How much safe airborne time does this equate to?

Landing Distance – What’s the minimum runway length you need to land safely with your current issue?

Aids (Landing Aids) – What’s the minimum category or type of landing you can make with the aircrafts current state?

Weather – What are the minimum weather conditions you can accept for an approach? (This will be dictated by your answer to the above question).

Having answers to all of the above will make life a lot easier when it comes to your decision making at the next stage. For all of the above questions, modern day aircraft and iPads are capable of calculating answers for you within moments. Once you have answers to those questions, it’s time to get more information about your realistic options. You already know how long you can remain airborne so you can rule out any airports beyond your flight time left. You know how much runway you need, so can potentially rule out any airports with runways not long enough.

In a scenario where you’re deciding to divert with an array of airfields to choose from, it’s wise to get current information for at least 3 or 4 options. The information you want should include the current weather, runway in use, and approach aids in use. This means you can very quickly compare each option with the requirements from your FLAW model to see which ones are suitable.

Option Generation Top Tips

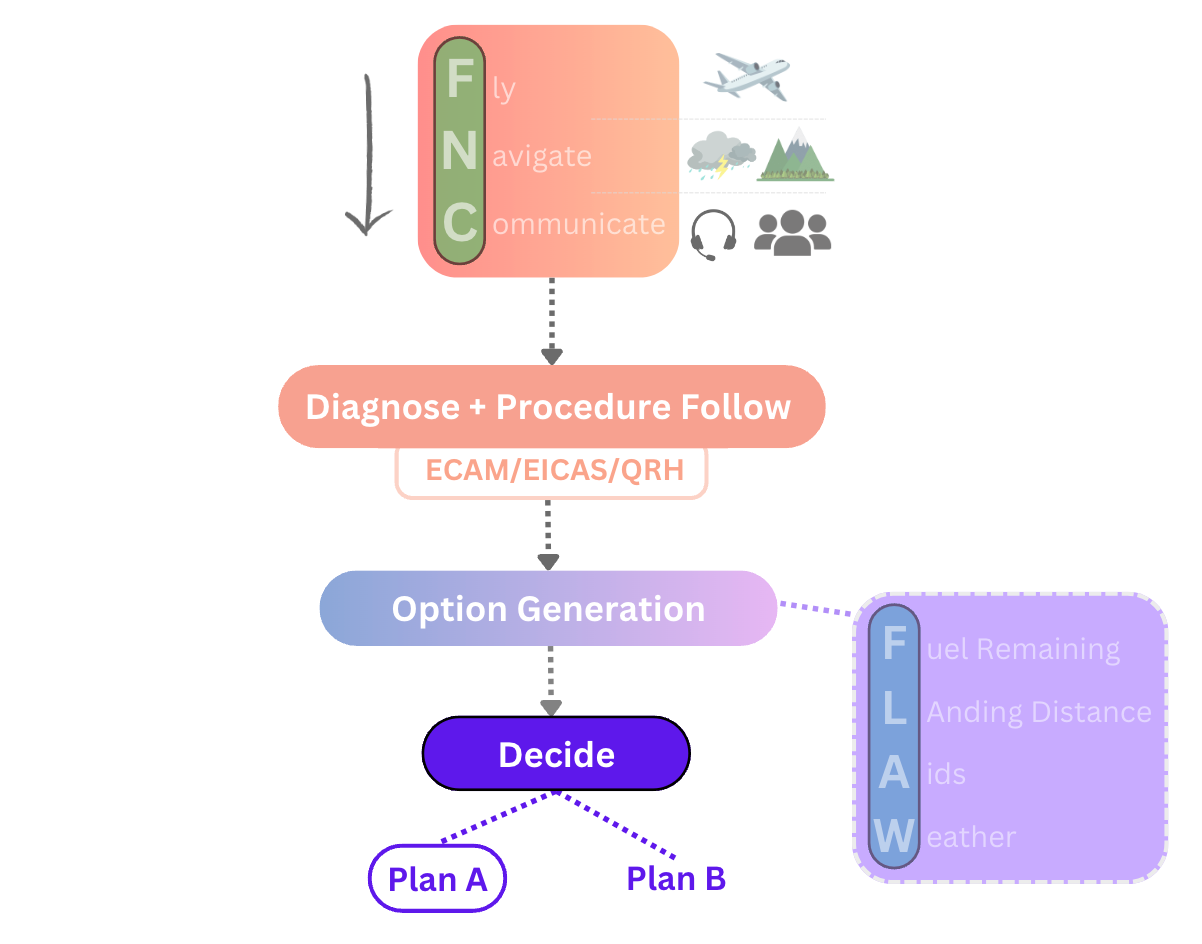

Decision time! With all the options laid out in front of you, it’s time to pull the trigger and decide which one’s the most appropriate. Many of these situations can be very ‘grey’, meaning there many not necessarily be a clearly defined ‘right’ decision. All you can do is use your knowledge and experience, along with the information in front of you at the time and the resources available to you, to make the most suitable decision.

Top Tips for Deciding

Decision made, now it’s a case of assigning tasks efficiently in order to prepare for the landing.

The list of tasks to assign may depend on how much time you have before needing to get on the ground. The first priority is still flying. As a captain, it’s often wise to assign this task to the FO for now as you’re about to have quite a lot of spinning plates to manage.

Again, ‘VLS’ is a great tool to help you deliver clear instruction to the first officer on where you want the plane to end up, and in what configuration. “Can you get the aircraft into a holding pattern on a 15 mile final, at 5000ft (crosscheck the chart for terrain clearance as you decide this height), at a speed of 250kts there then slowing to 220kts as we enter the hold”. Obviously, you’ll be monitoring the progress of this, but it’s one less thing for you to be hands on with.

What tasks are you going to assign to yourself? With the first officer flying, your main focus now is going to be on communicating of your new plan of action to those who need to know, along with setting the aircraft up for the approach. So, who now needs to know of this new plan?

Now time to set up the aircraft’s computer systems for the approach (this would be prioritised appropriately with communicating the plan to various parties). This will require programming ‘the box’ and referencing it from your charts. You should be building your own situational awareness of the approach as you do this and thinking through what needs to happen during the approach and in what order.

Once the box is ready, it’s time to brief the FO, and for this we follow a standard briefing format (which I’ll go into in another post). Bear in mind that as you’re likely in a non-normal situation here, the ‘threats’ part of the brief, along with the ‘how to fly it’ may take substantially longer than normal. It’s a good idea here to have any applicable QRH summaries out to refer to, along with any helpful documentation that dictate any special procedures for the approach.

Ensure you brief as thoroughly at time permits; what configuration and speed do you want to be at which points and why? Sharing this now means both crew members will be sharing the same mental model on the approach and errors can be picked up easier.

Some people tend to end this brief at the landing stage, but I believe it’s imperative to brief further than this; What’s the plan if you go around? What are you expecting to happen after landing? If the aircraft is in a non-normal state or you’re conducting an emergency landing, both of these points are important. Could it be an idea to request an alternative go-around procedure if the standard one’s very complex and you’ve lost a few systems? How will you play things after landing? Will you stop on the runway? Will you taxi straight to the gate? What alert calls will you be making to the cabin crew? It’s really useful to have discussed and thought about what’s going to happen ahead of time.

Brief complete, it’s time for the final review. This is an important but often forgotten part of the structure. It’s a great opportunity to check you haven’t missed anything and are still making a suitable decision, as well as ensuring both pilots really are on the same page. I find it highly beneficial at this stage to ask the FO to do the review and verbalize it. A quick reminder on what the issue is, what the main implications are, what we’re doing about it and how we’re going to do it, along with what our plan B is.

If the captain chooses to fly the approach and landing, it’s a good idea to take control of the aircraft just before the FO does this review, so the FO has the capacity to catch any errors as they run through things. If the FO is doing a stelar job of handing the aircraft and you want to keep it that way, just try to ensure the review’s not being done whilst they’re at a critical or very busy stage of flight, as it’s likely their capacity to listen may be hindered.

Now it’s time to fly the thing!

Prepare/Assign Top Tips

When I started in the airlines, we were taught the DODAR, or TDODAR model. This model works well as a basic structure and the model I’ve described above incorporates the DODAR model behind the scenes, with a few handy extras added on.

As a reminder, (T)DODAR is;

Time – How much fuel/time have we got?

Diagnosis – What’s the issue and therefore implications?

Options – What are our options for landing?

Decide – Chose a plan A and B

Assign – Assign tasks

Review – Final recap

When starting out as an FO I used to religiously follow the DODAR model and whilst it served Its purpose, I’ve found following the framework I’ve gone through above in much more detail, a more effectively way of working through failures.

I’ve put together a failure crib sheet, designed by myself on my command course as a template to help you manage failures effectively. It’s not official and not SOP, but it’s something I used throughout my training and really helped.

The sheet includes an example of how to fill it in, along with blank copies for you to print out.

You can download these sheets for free from PilotBible here.

Overall, I’ve found the above framework to be extremely helpful across all failure management scenarios I’ve encountered. It’s important to mention that you don’t HAVE to methodically follow every single step of it. All situations are dynamic and different, some will require more or less time spent in certain areas of the framework, some may require no time spent at all in certain areas. However, it’s a great structure to have in the back of your head (& on paper!) to help you effectively and efficiently manage scenarios as a pilot.

Last year, I had a medical emergency on board the aircraft I was in command of. We were crossing the Alps in darkness at 38,000ft, 12 hours into a long and tiring day.

Whilst this example isn’t necessary about managing a ‘failure’ as such, I used the above framework to effectively manage the situation and have us safely on the ground 15 minutes after being told by an onboard doctor that the passenger needed immediate medical attention. Suddenly having to descend through mountainous terrain, at night, towards the end of a very long working day is not an ideal situation, however following the structure ensured that the correct decisions were made, and that the safety of the aircraft was never compromised.

Somehow, an ATC recording of the incident end up online, found here. I’d like to share it with you as it’s a good example of putting many of the above tips into action and of good teamwork from multiple parties.

Jumping back to some of the tips above, you can actually hear the end of my last slow deep breath on the radio before I make the initial call declaring the Pan, which helped make my pan call clear, calm and concise. In return, it meant the superb Swiss ATC could offer us an immediate descent and heading as they had all the initial information they needed. By this point, myself and the FO had already done some option generation, come up with Zurich as plan A, (with an alternative for plan B) and I’d handed him control of the aircraft.

You can hear the FO takeover the radio’s part way through the descent, whilst I’m giving a NITS brief to our cabin crew, and then again whilst I’m doing a PA to the passengers. As we turn base leg the FO takes the radios for the remainder of the flight as I chose to fly the approach due to reasons explained in the full story here.

Although some parts of the readbacks are actually cut from the video, and others are slightly unclear due to the interference (that interference wasn’t present in our radios), hopefully you’ll notice the communication from both sides of the flightdeck and ATC are clear, concise and relevant. No unnecessary chat or information.

You then hear us thinking ahead and asking which parking stand we’ll be on. This was so we can we figure out where would be best to come off the runway to ensure we get to the stand as expeditiously as possible and could quickly brief the potential taxi routing.

Example; US Airways 1549; Landing on The Hudson

A very well-known real life example where FNC was used really well is Sully’s Hudson event. From the video below, you can see he absolutely prioritises flying the aircraft and navigating, even creating his own ‘mini-plan’ in this case to turn towards La Guardia, before saying anything to ATC. When they do make that radio call, it’s clear, precise, and just saying what ATC need to know. It’s also ‘telling’ ATC what they’re doing as opposed to asking permission. In time pressured situations like this, it’s sometimes necessary to use common sense and airmanship.

The crew absolutely lead the situation, as opposed to ATC leading them. There are several ATC calls that the crew don’t respond to as they’re correctly prioritising flying the aircraft rather than responding. They use ATC as a resource i.e asking about other airport options. They come back to FNC and change their plan as new information is brought to light (that they can’t make the return to La Guardia, then again when they can’t make Teterboro).

During the initial ‘Fly’ stage they still glanced down to understand what had happened (lost both engines) which as necessary to dictate the trajectory they put the aircraft on, but they ensured they didn’t get ‘sucked in’ to the ECAM. They struck a fine balance by managing to action the only checklist which gave them a fighting chance of relighting an engine, whilst pilot flying was absolutely focussing on nothing but the flying and navigating.

In another insightful video, Captain Sully goes into more detail about exactly what he focussed on during those moments and why he decided to ignore other things that were essentially distractions. Essentially it boils back down to FNC, prioritising affectively and following a solid but adaptable failure management framework.

I hope the above article helps to give new pilots an understanding of how to effectively manage failures by following a framework, as well as giving insights and new perspectives to current pilots. Please feel free to comment below if you have any thoughts!

This article was written by Sam Todman (a current Airline Captain in the UK) and published by PilotBible.

Enjoyed this post? Add your email below & we’ll notify you each time relevant posts go live

Learn how to become an airline pilot in 2026 with this updated guide. Training routes, costs, MPL vs ATPL, funding options, and airline advice.

When disaster strikes at 38,000 feet, split-second decisions save lives. Behind every pilot during an emergency lies hundreds of hours of rigorous training. How do airlines prepare flight crews to handle the unexpected? The answer reveals an intense world few passengers ever witness.